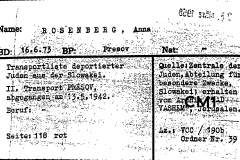

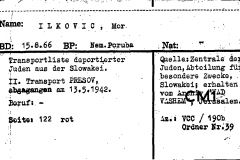

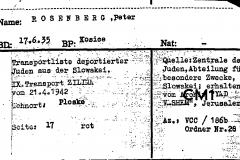

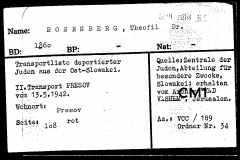

World War II reached Judita’s family in March 1944 when German troops occupied Hungary. Judita’s aunt, uncle and 6-year old cousin were deported on April 21, 1942 from Slovakia to Auschwitz. Judita’s grandparents were deported May 13, 1942 from Presov, Slovakia to Auschwitz, and her parents were deported on May 20, 1944, from the Hungarian countryside to Auschwitz. Her grandfather, who was in poor health, died in the cattle car while in route to the Auschwitz; the rest of her family perished in the camp.

While their parents and grandparents were being transported to Auschwitz, Judita and her brother Denes were attending school in Budapest and living in a “Star House.” These houses were marked with a yellow star to indicate Jewish residents, who were subject to certain rules. Judita, Denes and the other residents developed routines in the Star House: abiding by a strict curfew, cooking with what limited ingredients they could acquire, and seeking shelter during daily air raid sirens.

Death March to Mauthausen Concentration Camp

Judita’s personal Holocaust began in October 23, 1944 when all young Jews were ordered to report for work digging trenches around Budapest. Nineteen-year old Judita arrived for work feeling strong and determined, but she was not prepared for the reality of what lay before her: a weeks-long death march and two concentration camps.

The death march towards Austria began on November 13, 1944. After walking for several hours in the cold rain Judita and the other young women arrived at their first destination, an airport with no roof. The women spent the night standing as icy rain water fell from above eventually reaching their knees. In the morning Judita saw bodies fall around her as the room emptied out. These women died during the night and were the first victims of the march. On November 22, 1944 they crossed the border into Austria at Zumdorf. Then they were loaded into freight cars and taken back to Hungary, to Koszeg camp where they dug trenches in the frozen ground.

On March 23, 1945 the sick and weak were killed in makeshift gas tents; the rest were marched to Rechnitz, Austria. The march continued to Mauthausen camp through western Hungary and Austria for 17 days (March 28-April 15, 1945). During the march Judita and the other prisoners were fed four times and drank from puddles on the side of the road to stay hydrated.

On the tenth day of the death march (April 7, 1945), Judita and her fellow prisoners climbed up a steep road into the mountains in Eisenerz, Austria. As they reached the top they heard gunshots and saw soldiers shooting at them and yelling, “rush, rush, Jewish pigs.” The German soldiers’ intent was clear: kill all the prisoners. With the Russians and Americans approaching, and with no need for the prisoners, the Germans identified the mountain road in Eisenerz as the perfect location for a mass execution. Judita ran from the gunshots screaming for her mother and thinking of all the life she had not yet lived. The shooting lasted for 40 minutes; 500 people were killed.

Judita and the other survivors of the Eisenerz massacre were forced to continue marching to Mauthausen camp. They arrived at the camp on April 14, 1945, and stayed there for 10 days. Mauthausen’s prisoners slept on the floor tightly packed into small tents. Two daily events broke the monotony: 1) one food delivery that consisted of soup (grayish dishwashing water) and one kilogram of moldy bread to be split among 10 prisoners; and 2) a walkthrough by the guards who came with a wheelbarrow to collect the dead bodies. Mauthausen was evacuated in late April, and on April 25, 1945 Judita and the surviving prisoners were evacuated and directed toward another camp, Gunskirchen.

Gunskirchen Concentration Camp

She reached the camp on April 28, 1945. The Nazis built Gunskirchen in a dense and swampy pine forest. The camp had no water, no latrines, and no bunks on which to sleep. Prisoners had to survive on only one cup of soup per day. Lack of food became so dire that some prisoners ate the flesh of the dead to avoid starvation. Judita recalls the all-consuming feeling of hunger. She felt the starvation in her bones and her brain, not her stomach. She could not think, nor remember a single song or poem. Her most painful moment was realizing that she could not recall her mother’s face. Prisoners awoke at 3 AM or 4 AM for head count and spent the day digging anti-tank trenches in the frozen ground. Prisoners at Gunskirchen were dying at a rate of 200 per day.

Judita and the other prisoners developed “camp smarts” to try and trick death. First, everything was edible. Judita ate grass, leaves, raw potato peels, and bread mold. Second, always keep a piece of bread until you get another. Judita followed this rule for five days at the longest. Third, sleep in a circle to maintain body heat during the cold winter nights (when sleeping in a row, the two prisoners at the end would be dead by morning). Fourth, inspect clothing and kill lice every night to avoid weakness from blood loss. It became a game among the prisoners to compete for the highest number killed with counts reaching into the hundreds.

On May 4, 1945 the U.S. Army liberated Gunskirchen. On August 2, 1945, the group was handed over to the Red Army and marched back east, without food and at risk of being shot for stealing potatoes from nearby fields. Judita escaped from the Russians and made her way back to Budapest on August 15, 1945.

Of the original group of 5,000 only 60 survived